This article was authored by Paul Goodwin of Watermark Marine Systems, LLC, and was published in the Winter 2020 issue of the NH LAKES quarterly newsletter Lakeside.

There are a lot of myths and misconceptions regarding de-icing around docks, breakwaters, and boathouses during the winter months. First and foremost, everyone seems to call these units something different. I’ve heard bubbler, aerator, circulator, pump, aquatherm, and de-icer used interchangeably for as long as I can remember. In the end, they all mean the same thing: some sort of mechanical or electrical device to keep the freezing ice from wrecking waterfront structures.

Let’s review the theory and physical properties of de-icing around a dock. One of the unique properties of water is that as it starts to freeze, its density changes. Around 39 degrees Fahrenheit, water reaches its maximum density, creating a flip-flop effect that brings less dense, slightly warmer water to the lake surface. This occurs until all the water in the lake cools to 39 degrees. From there, the surface water continues to cool to 32 degrees (the point at which water is its least dense) and it expands to form ice. This is why lakes, ponds, and rivers freeze only on the surface and fish can survive in the relatively warm water below.

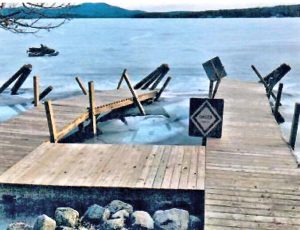

During the winter months, the ice expands and moves around. If a dock is frozen in the ice, it is likely to be damaged. If the water levels are low, and the ice rises due to rain and inflow, then pilings can be pulled out of the lake bottom. It is this combination of factors which causes the ‘ski jump’ type damage often seen on piling docks in the spring. The goal with de-icing is to open-up just enough water to keep structures disconnected from the ice sheet, but only enough to accomplish this separation.

It’s important to understand that a de-icer only prevents ice damage due to freezing expansion and water level changes. A de-icer does not protect a structure from large ice floes moving randomly around in the spring. Spring floe ice is best counteracted with ice protection pilings or by removing a dock. Some areas of our lakes are more regularly susceptible to ice floe damage from year to year. Of course, ‘ice out’ and the thawing process is not an exact science, so almost any structure can be at risk from ice floes.

Years ago, and this is the origin of the words ‘bubbler’ and ‘aerator,’ small air compressor pumps were used on docks during the freezing months and a garden hose-like pipe was wound around the structure, resting on the lake bottom. The air flow through the hose, which had numerous pin-holes along its length, allowed air bubbles to escape and race to the surface, bringing up warm water and causing weak spots or open water in the ice at the surface. These compressors ran non-stop and were relatively noisy. Neighbors were typically unhappy with the cumulative noise and often a cover was constructed to make them quieter. Covers could cause units to overheat and fail and, once the ice refroze, it was usually impossible to restore open water. One advantage of this type of unit was the relatively small amount of open water at the surface; however, as they ran constantly, they were not energy efficient.

Most people today are probably more familiar with the propeller-type aerator units. These can be floating, hanging, bottom mounted, or dock mounted. These types of units can open an incredible amount of ice, if run constantly. These work by bringing relatively warm water up from the bottom and pushing it around the docks via the spinning propeller.

So, the question everyone asks is: what will work best for me? Unfortunately, there is no easy or correct answer. Each site is affected by freezing ice differently and one must consider a number of factors, such as, winter uses, sun exposure, currents, depth contours, prevailing winds, and other site specific factors to maximize efficiency and minimize too much open water. Do you like to snowmobile, ice fish, or skate and need safe access to the ice? Do you have a long dock, wide dock, or a special shorefront consideration? Are you around in the winter to monitor the ice? All these factors must be considered in choosing your best alternative.

We suggest having someone available to monitor your ice protection gear and starting out with either a bottom mount circulator in shallow water and a hanging unit in deeper water. By actively managing the circulators during the changing season, you can control the amount of open water and electricity used. Using a timer and a thermostat will allow you to accurately regulate the open water around your dock. Every site is unique. Through some simple experimentation and intelligent management of your ice protection gear, you can custom tune de-icing to your specific conditions without stirring up sediment or undermining structures. You will save a considerable amount of electricity and reduce the amount of open water around your shoreline structures, too!

BE ADVISED: If you operate a de-icing unit…Effective July 14, 2019, the New Hampshire Legislature passed House Bill 668 which amended RSA 270:33. This amendment restricts the placement and operation of “aquatherms” to limit open water to directly in front of a lakefront owner’s property. Additionally, “THIN ICE” signs must be visible from ALL directions approaching the area, which means a minimum of three signs, arranged in a triangle so as to be visible from all angles. As in the past, all shoreline de-icing equipment operation requires registration with the New Hampshire Department of Safety under RSA 270:34. Registration forms are available from your local Town or City Clerk for $0.50.

A power failure for my circulator resulted in dock freezing in. I have restored power, but there is a lot of ice. If I turn on the circulator now, is it likely to de-ice?